If you've read my blog before, you know that memory safety is a huge unsolved problem, and that there's a vast unexplored space between the various memory safety models. The discerning eye can infer that we're starting to see the lines blur between these seemingly unrelated memory safety approaches.

This is ridiculously exciting to me, because today's popular memory-safe languages are very limited: they're fast, or they're flexible, but not both. Finding new blends is an incredibly challenging and worthy endeavor... one which has claimed the sanity of many explorers.

A few of us have been approaching the problem by starting with reference counting or garbage collection (or generational references!) and allowing functions to "borrow" those objects with much less--or zero--overhead. 0

In my biased 1 opinion, these approaches have some strong benefits. But they're not a panacea, and the world needs more approaches here.

And luckily, my good friend Nick Smith (from the Mojo community 2) has been exploring exactly that for the past few years.

I think he's found a way to add mutable aliasing directly into a borrow checker without building on a foundation of reference counting, garbage collection, or generational references. In other words, an approach for zero-overhead mutable aliasing, which is a big deal. 3

After reading his original explanation here, I knew that it should definitely be more widely known. He's graciously allowed me to take a shot at explaining it, so here we are!

I'll try to explain the approach as simply as possible, but if you have any questions, Nick can be found in the Mojo server (username nick.sm), or feel free to ask me in the r/vale subreddit or the Vale discord's #languages channel. And if you find this interesting, consider sponsoring Nick!

Also, this article is gloriously long and has a lot of context, so I'll let you know when to skip ahead.

For example, blending GC with arenas, blending RC with region borrowing, or Vale's approach of blending generational references with region borrowing, and so on.

My language Vale uses one of these approaches, so I'm of course biased to see its benefits more strongly than others!

Disclaimer: I work on the Mojo team at Modular! But I'll keep this post more about Nick's discovery in general, rather than how it would do in any specific language.

My long-time readers will recognize my cognitive dissonance here because I think such a thing is a myth. Nick's approach makes me question that, though. At the very least, we're much closer to achieving the myth, if he hasn't solved it completely already.

Foundation: Builds on C++'s "Single Ownership"

TL;DR: Nick's approach is based on single ownership, like C++ and Rust. Every value is "owned" by a containing object, array, stack frame, or global.

If you know how C++ and Rust work already, skip ahead!

If you don't know, or just like reading, I'll explain what single ownership is.

For example if we have this C++ program:

#include <vector>

struct Engine { int fuel; };

struct Spaceship { unique_ptr<Engine> engine; };

void foo(vector<Spaceship>* ships) { ... }

void main() {

vector<Spaceship> ships;

...

foo(&ships);

}...we can say this:

- main's stack frame "owns" vector<Spaceship> ships;

- The vector<Spaceship> ships; owns each Spaceship.

- Each Spaceship owns its Engine (via the unique_ptr).

- Each Engine owns its int fuel;

-

foo does not own the vector

, it just has a raw pointer. - main's stack frame owns foo's stack frame.

- main is the only thing without an owner.

If you've coded in C++ or Rust, you're probably familiar with this mindset.

If you've coded in C, you might think like this too, even though C doesn't explicitly track single ownership. If you trace an object's journey all the way from its malloc() call to its free() call, all of the variables/fields that the pointer passes through are dealing with the "owning pointer", so to speak. It's almost like how detectives track the "chain of custody" for evidence. In other words, who is responsible for it at any given moment.

Heck, even Java and C# programmers sometimes think in terms of single ownership. If you're supposed to call an object's "dispose"/"cleanup"/"destroy"/"unregister"/etc. method at some point, you can trace that object's journey all the way from new to that (conceptually destructive) method call, and those are the variables/fields that are handling its "owning reference", so to speak.

Single ownership, as explained so far, is the foundation for a lot of languages:

- If you add regular (unrestricted) pointers and references, you get C++.

- If you add generational references and region borrowing, you get Vale.

- If you add "aliasable-xor-mutable" references, you get Rust.

- If you add "group borrowing", you get Nick's system.

Nick's system is the main topic of this article, but for some context, and to know why Nick's system stands out, let's take a quick detour to recap how Rust's borrow checking works.

Recap of Rust Borrowing

To truly appreciate Nick's approach, it's helpful to know the limitations of Rust's borrow checker.

TL;DR: Rust's borrow checker has the "aliasing xor mutable" rule which makes it conservative. This means it rejects a lot of valid programs and useful patterns 4 and it causes accidental complexity for some use cases. 5 If Nick's approach can solve even some of these pain points, that's a pretty exciting step forward.

If you're already familiar with Rust's limitations, skip ahead to Nick's approach!

If not, here's a very simplified explanation of Rust's borrow checking, and I'll overview the limitations in the next section.

I'll assume some knowledge of modern C++, but if you're primarily a C programmer, check out this post instead.

There are two kinds of references: readwrite, and readonly. These are often called "mutable" and "immutable" (or more accurately "unique" and "shared") but for now, think of them as readwrite and readonly.

There are a few ways to get a readwrite reference:

- If you own an object, you can get a single temporary "readwrite" reference for a certain scope (function body, loop body, then/else body, etc). During this scope, you can't access the original object directly, you must use that reference.

- If you have a readwrite reference to an object (a struct, collection, etc.), you can get a readwrite reference to one of its fields (or elements) for a certain scope. During this scope, the original reference can't be used.

Using these is pretty restrictive. Because of that first rule:

- You can never have two usable readwrite references to the same object in the same scope.

- You can never have two usable readwrite references to an object and its field at the same time. In other words, while you have a readwrite reference to a Spaceship's Reactor, you can't read or write that Spaceship.

Now, let's introduce "readonly" references. They operate by different rules:

- If you have a readwrite reference, you can get any number of temporary "readonly" references for a certain scope. During this scope, the readwrite reference is inaccessible.

- In a scope, if you have an readonly reference to an object (a struct, collection, etc.), you can get a readonly reference to one of its fields (or elements) for that scope.

Rust adds some quality-of-life improvements to make this a little easier. For example, you can get a bunch of immutable references directly from an owned object. It's actually not that bad if you're writing a program that inherently agrees with the rules, like compilers, games using ECS, stateless web servers, or generally anything that transforms input data to output data.

Like observers, intrusive data structures, back-references and graphs (like doubly-linked lists), delegates, etc.

Like mobile/web apps, games using EC, or stateful servers... generally, things that inherently require a lot of state.

Context and Comments on Borrow Checking Limitations

One can't improve on a paradigm unless they know its limitations. So let's talk about borrow checking's limitations!

Because of those "inaccessible" rules, we can never have a readwrite reference and a readonly reference to an object at the same time. This restriction is known as "aliasability xor mutability".

In theory this doesn't sound like a problem, but in practice it means you can't implement a lot of useful patterns like observers, intrusive data structures, back-references, graphs (like doubly-linked lists), delegates, etc. and it causes accidental complexity for use cases like mobile/web apps, games using EC, or stateful servers... generally, things that inherently require a lot of state.

And besides, borrow checking is generally worth it, because it means we get memory safety without run-time overhead.

Well, mostly.

Like I explain in this post, it's not really free; even if you avoid Rc/RefCell/etc., borrow checking can often incur hidden costs, like extra bounds checking or potentially expensive cloning and hashing.

The borrow checker has long been known to reject programs that are actually safe, causing you to add and change code to satisfy its constraints. When this happens, one might just shrug and say "the borrow checker is conservative," but in reality, the borrow checker is imposing accidental complexity.

And besides, we know that mutable aliasing doesn't conflict with zero-cost memory safety, as we learned from the Arrrlang thought experiment. The only question is... can we get the best of both worlds?

Perhaps! It's not certain, even with Nick's approach. But with enough innovation in this space, I think we can get there.

An example

(Or skip ahead to Nick's approach if you understood the above!)

Here's an example (source):

struct Entity {

hp: u64,

energy: u64,

}

impl Entity { ... }

fn attack(a: &mut Entity, d: &mut Entity) { ... }

fn main() {

let mut entities = vec![

Entity { hp: 10, energy: 10 },

Entity { hp: 12, energy: 7 }

];

attack(&mut entities[0], &mut entities[1]);

}Rust rejects this, giving this output:

error[E0499]: cannot borrow `entities` as mutable more than once at a time

--> src/main.rs:35:35

|

35 | attack(&mut entities[0], &mut entities[1]);

| ------ -------- ^^^^^^^^ second mutable borrow occurs here

| | |

| | first mutable borrow occurs here

| first borrow later used by call

|

= help: use `.split_at_mut(position)` to obtain two mutable non-overlapping sub-slicesAlas, .split_at_mut isn't always great in practice (reasons vary) 6 and besides, we sometimes want to have two &mut referring to the same object.

The more universal workaround is to use IDs and a central collection, like this (source, uses slotmap):

fn attack(

entities: &mut SlotMap<DefaultKey, Entity>,

attacker_id: DefaultKey,

defender_id: DefaultKey

) -> Result<(), String> {

let a = entities

.get(attacker_id)

.ok_or_else(|| "Attacker not found in entities map".to_string())?;

let d = entities

.get(defender_id)

.ok_or_else(|| "Defender not found in entities map".to_string())?;

let a_energy_cost = a.calculate_attack_cost(d);

let d_energy_cost = d.calculate_defend_cost(a);

let damage = a.calculate_damage(d);

let a_mut = entities

.get_mut(attacker_id)

.ok_or_else(|| "Attacker not found in entities map".to_string())?;

a_mut.use_energy(a_energy_cost);

let d_mut = entities

.get_mut(defender_id)

.ok_or_else(|| "Defender not found in entities map".to_string())?;

d_mut.use_energy(d_energy_cost);

d_mut.damage(damage);

Ok(())

}This is using the slotmap crate (similar to generational_arena), though you often see this pattern with HashMap instead (or one could also use raw indices into a Vec, though that risks use-after-release problems).

If you want it to be more efficient, you might be tempted to get two mutable references up-front:

fn attack(

entities: &mut SlotMap<DefaultKey, Entity>,

attacker_id: DefaultKey,

defender_id: DefaultKey

) -> Result<(), String> {

let a = entities

.get_mut(attacker_id)

.ok_or_else(|| "Attacker not found in entities map".to_string())?;

let d = entities

.get_mut(defender_id)

.ok_or_else(|| "Defender not found in entities map".to_string())?;

let a_energy_cost = a.calculate_attack_cost(d);

let d_energy_cost = d.calculate_defend_cost(a);

let damage = a.calculate_damage(d);

a.use_energy(a_energy_cost);

d.use_energy(d_energy_cost);

d.damage(damage);

Ok(())

}But alas, rustc complains:

error[E0499]: cannot borrow `*entities` as mutable more than once at a time

--> src/main.rs:34:13

|

31 | let a = entities

| -------- first mutable borrow occurs here

...

34 | let d = entities

| ^^^^^^^^ second mutable borrow occurs here

...

37 | let a_energy_cost = a.calculate_attack_cost(d);

| - first borrow later used here...because we're mutably borrowing entities twice: once in a's get_mut call, and once in d's get_mut call, and their usages overlap.

Or, said differently, it's worried that a and d might be pointing to the same Entity, thus violating aliasability-xor-mutability.

But why is a compiler telling me that an Entity can't attack itself? That's odd, because in this game, that's totally allowed. Even pokémon can hurt themselves in their confusion.

One might say, "because that's a memory safety risk!" But that's not necessarily true. From what I can tell, that code would be just fine, and not risk memory safety. And in fact, Nick's system handles it just fine.

So let's take a look at Nick's system!

For example, if you need N references instead of just 2, or they don't need to be / shouldn't be distinct, or you want to still hold a reference while also holding those N references, etc.

Nick's Borrowing System

As I explain Nick's system, please keep in mind:

- I'm taking some terminology liberties: the proposal calls them "regions", but here I'm describing them as "groups", mainly because I know that "regions" tends to get misinterpreted as "arenas". These are not arenas. 7

- This proposal is from about a year ago, and Nick's been working on an even better iteration since then that's not ready yet. Subscribe to the RSS feed because I'll be posting about Nick's next proposal when it comes!

- Nick's proposal is for Mojo, so the code examples are modified Mojo syntax.

Our goal is to write something like the Rust attack function from the last section:

fn attack(

entities: &mut SlotMap<DefaultKey, Entity>,

attacker_id: DefaultKey,

defender_id: DefaultKey

) -> Result<(), String> {

let a = entities

.get(attacker_id)

.ok_or_else(|| "Attacker not found in entities map".to_string())?;

let d = entities

.get(defender_id)

.ok_or_else(|| "Defender not found in entities map".to_string())?;

let a_energy_cost = a.calculate_attack_cost(d);

let d_energy_cost = d.calculate_defend_cost(a);

let damage = a.calculate_damage(d);

let a_mut = entities

.get_mut(attacker_id)

.ok_or_else(|| "Attacker not found in entities map".to_string())?;

a_mut.use_energy(a_energy_cost);

let d_mut = entities

.get_mut(defender_id)

.ok_or_else(|| "Defender not found in entities map".to_string())?;

d_mut.use_energy(d_energy_cost);

d_mut.damage(damage);

Ok(())

}But we're going to write it with memory-safe mutable aliasing, so it's simpler and shorter!

A sneak peek of what it would look like:

fn attack[mut r: group Entity](

ref[r] a: Entity,

ref[r] d: Entity):

a_power = a.calculate_attack_power()

a_energy_cost = a.calculate_attack_cost(d)

d_armor = d.calculate_defense()

d_energy_cost = d.calculate_defend_cost(a)

a.use_energy(a_energy_cost)

d.use_energy(d_energy_cost)

d.damage(a_power - d_armor)I'll explain Nick's system in four steps:

- Basic mutable aliasing

- References to an object vs its contents

- Child groups, which blur that distinction a bit

- Group annotations, which help inter-function reasoning a bit

We'll start simple, and build up gradually.

I know this from experience. I regret naming Vale's regions "regions"!

Basic Mutable Aliasing

Let's start by completely forgetting the difference between readonly and readwrite references. Let's say that all references are readwrite.

Now, take this simple Mojo program that has two readwrite aliases to the same list:

fn example():

my_list = [1, 2, 3, 4]

ref list_ref_a = my_list

ref list_ref_b = my_list

list_ref_a.append(5)

list_ref_b.append(6)Here's the equivalent Rust code:

fn example() {

let mut my_list: Vec<i64> = vec![1, 2, 3, 4];

let list_ref_a = &mut my_list;

let list_ref_b = &mut my_list;

list_ref_a.push(5);

list_ref_b.push(6);

}The Rust compiler rejects it because we're violating aliasability-xor-mutability, specifically in that we have two active readwrite references:

error[E0499]: cannot borrow `my_list` as mutable more than once at a time

--> src/lib.rs:4:22

|

3 | let list_ref_a = &mut my_list;

| ------------ first mutable borrow occurs here

4 | let list_ref_b = &mut my_list;

| ^^^^^^^^^^^^ second mutable borrow occurs here

5 |

6 | list_ref_a.push(5);

| ---------- first borrow later used hereBut... we humans can easily conclude this is safe. After the evaluation of list_ref_a.push(5), my_list is still there, and it's still in a valid state. So there is no risk of memory errors when evaluating the second call to push.

In any language, when we hand a function a non-owning reference to an object, that function can't destroy the object, 8 nor change its type. The same is true here.

Therefore, the caller should be able to have (and keep using) other references to that object, and it's totally fine.

Nick's approach handles this by thinking about "a reference to an object" as different from "a reference to its contents". We can have multiple references to an object, but references into an object's contents will require some special logic.

I'll explain that more in the next section.

If a language supports temporarily destroying a live object's field, like Mojo, Nick's model supports that as well. It tracks that "some object in this group is partially destroyed" and temporarily disables other potential references to that object while that's true.

When to Invalidate References to Contents

So how do we handle a caller's references to the contents of the object? What kind of special logic does that require?

In the below example, the compiler should reject print(element_ref) because append might have modified the List.

fn example():

my_list = [1, 2, 3, 4]

ref list_ref = my_list

ref el_ref = my_list[0]

list_ref.append(5)

print(el_ref)It would be amazing if a memory safety approach knew that the previous example was fine and this one isn't.

In other words, the approach should know that when we hand append a reference to List, it shouldn't invalidate the other reference list_ref, but it should invalidate any references to its contents (like el_ref).

I like how Nick put it in his proposal:

If I had to boil it down to one sentence, I'd say: When you might have used a reference to mutate an object, don't invalidate any other references to the object, but do invalidate any references to its contents.

Following this general rule, a lot of programs are revealed to be safe.

And this isn't that crazy; if you've used C++ a lot, this likely agrees with your intuition.

Note that we'll relax this rule later, and replace it with a more accurate one. But for now, it's a useful stepping stone.

A More Complex Example

Above, I gave a sneak peek at an attack function.

Let's look at it again:

fn attack[mut r: group Entity](

ref[r] a: Entity,

ref[r] d: Entity):

damage = a.calculate_damage(d)

a_energy_cost = a.calculate_attack_cost(d)

d_energy_cost = d.calculate_defend_cost(a)

a.use_energy(a_energy_cost)

d.use_energy(d_energy_cost)

d.damage(damage)For now:

- Ignore the [mut r: group Entity], we'll get to that later.

- Know that none of these methods delete any Entitys. 9

- Know that the damage call modifies d, and the use_energy calls modify a and d. Nothing else modifies anything.

(I'll explain both of those points more later.)

Note how this function isn't holding any references to Entitys' contents... only to whole Entitys.

All these methods don't delete any Entitys, so this attack function is completely memory safe. In fact, even though the use_energy and damage methods modify Entitys, every line in attack is still memory-safe. 10

Let's look at this alternate example now to see it catching an actual memory safety risk.

Entity looks like this now:

struct Entity:

var hp: Int

var rings: ArrayList[Ring]

...attack now holds a reference to an Entity's contents, like so:

fn attack[mut r: group Entity](

ref[r] a: Entity,

ref[r] d: Entity):

ref ring_ref = d.rings[0] # Ref to contents

damage = a.calculate_damage(d)

a_energy_cost = a.calculate_attack_cost(d)

d_energy_cost = d.calculate_defend_cost(a)

a.use_energy(a_energy_cost)

d.use_energy(d_energy_cost)

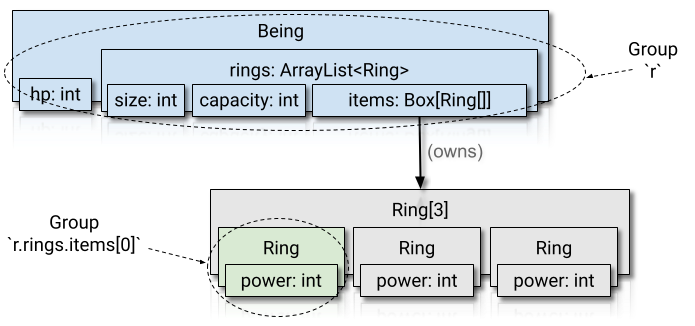

...The compiler views the program like this:

The compiler knows that:

- There is a r group (in blue).

- There is a r.rings.items[0] group (in green).

- The r.rings.items[0] group (green) is a child of group r (blue).

Now let's see what happens when we modify d with a call to damage and then try to use that ring_ref:

ref ring_ref = d.rings[0] # Ref to contents

damage = a.calculate_damage(d)

a_energy_cost = a.calculate_attack_cost(d)

d_energy_cost = d.calculate_defend_cost(a)

a.use_energy(a_energy_cost)

d.use_energy(d_energy_cost)

d.damage(damage)

print(ring_ref) # Invalid, should show errorThe compiler shows an error, because one of the functions (like damage) might have deleted that first ring, so the compiler should invalidate any references to the contents of all Entitys in the group.

We're really just following the rule from before: When you might have used a reference to mutate an object, don't invalidate any other references to the object, but do invalidate any references to its contents.

More precisely, these methods are only able to access the entities in group r by going through the variables a and d. In other words, there are no "back channels" for gaining access to the entities. This is important for memory safety and also for optimizations' correctness.

I'd like to remind everyone that this is all theoretical. Let me know if you have any improvements or comments on the approach!

Child groups

That's a useful rule, and it can get us pretty far. But let's make it even more specific, so we can prove more programs memory-safe.

For example, look at this snippet:

ref hp_ref = d.hp # Ref to contents

damage = a.calculate_damage(d)

a_energy_cost = a.calculate_attack_cost(d)

d_energy_cost = d.calculate_defend_cost(a)

a.use_energy(a_energy_cost)

d.use_energy(d_energy_cost)

d.damage(damage)

print(hp_ref) # Valid!The previous (invalid) program had a ring_ref referring to an element in a ring array.

This new (correct) program has an hp_ref that's pointing to a mere integer instead.

This is actually safe, and the compiler should correctly accept this. After all, since none of these methods can delete an Entity, then they can't delete its contained hp integer.

Good news, Nick's approach takes that into account!

But wait, how? Wouldn't that violate our rule? We might have used a reference (damage may have used d) to mutate an object (the Entity that d is pointing to). So why didn't we invalidate all references to the Entity's contents, like that hp_ref?

So, at long last, let's relax our rule, and replace it with something more precise.

Old rule: When you might have used a reference to mutate an object, don't invalidate any other references to the object's group, but do invalidate any references to its contents.

Better rule: When you might have used a reference to mutate an object, don't invalidate any other references to the object's group, but do invalidate any references to anything in its contents that might have been destroyed.

Or, to have more precise terms:

Even better rule: When you might have used a reference to mutate an object, don't invalidate any other references to the object's group, but do invalidate any references to its "child groups".

So what's a "child group", and how is it different from the "contents" from the old rule?

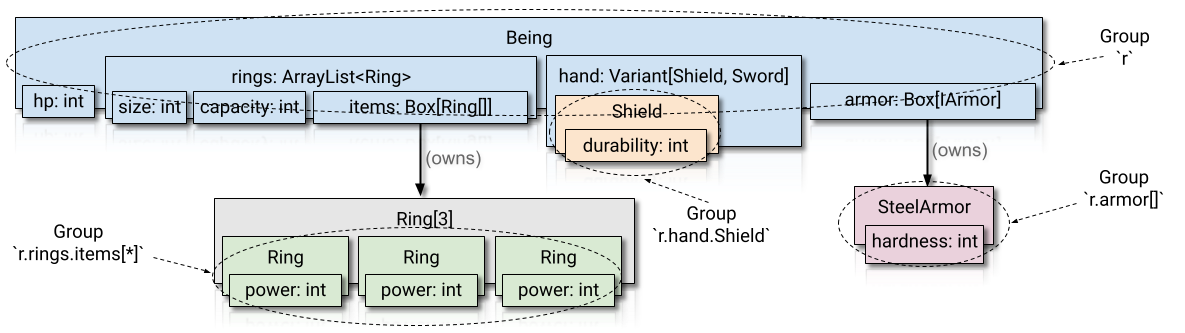

If Entity was defined like this:

struct Entity:

var hp: Int

var rings: ArrayList[Ring]

var armor: Box[IArmor] # An owning pointer to heap (C++ "unique_ptr")

var hand: Variant[Shield, Sword] # A tagged union (Rust "enum")

struct Ring:

var power: int

struct Shield:

var durability: int

struct Sword:

var sharpness: int

struct SteelArmor:

var hardness: intThen these things would be part of an Entity's group:

However, these would be in Entity's child groups:

- The Rings inside that rings list.

- The IArmor object that armor points to.

- The Shield or Sword inside the hand variant.

For example, if we had this code:

fn attack[mut r: group Entity](

ref[r] a: Entity,

ref[r] d: Entity):

ref hp_ref = d.hp

ref rings_list_ref = d.rings

ref ring_ref = d.rings[rand() % len(d.rings)]

ref armor_ref = d.armor[] # Dereferences armor pointer

match ref d.hand:

case Shield as ref s:

...Then these are the groups the compiler knows about:

Some observations:

- d, hp_ref, and rings_list_ref all point to the r group (in blue).

- ring_ref points to the r.rings.items[*] group (in green). That group represents all the rings, because the compiler doesn't know the index rand() % len(d.rings). This is different than the r.rings[0] from before.

- armor_ref points to the r.armor[] group (in red).

- s points to the r.hand.Shield group (in yellow). 13

As a user, you can use this rule-of-thumb: any element of a Variant or a collection (List, String, Dict, etc) or Box will be in a child group.

That all sounds abstract, so I'll state it in more familiar terms: if an object (even indirectly) owns something that could be independently destroyed, it must be in a child group.

Now, let's see what happens to the groups when we add a damage call in. Remember: Entity.damage mutates the entity, so it has the potential to destroy the rings, armor, shields and/or swords that the entity is holding:

fn attack[mut r: group Entity](

ref[r] a: Entity,

ref[r] d: Entity):

ref hp_ref = d.hp # Group r

ref rings_list_ref = d.rings # Group r

ref ring_ref = d.rings[rand() % len(d.rings)] # Group r.rings.items[*]

ref armor_ref = d.armor[] # Group r.armor[]

match ref d.hand:

case Shield as ref s: # Group r.hand.Shield

...

d.damage(10) # Invalidates refs to r's child groups

# Group r.rings.items[*] is invalidated

# Group r.armor[] is invalidated

# Group r.hand.Shield is invalidated

print(hp_ref) # Okay

print(len(rings_list_ref)) # Okay

print(ring_ref.power) # Error, used invalidated group

print(s.durability) # Error, used invalidated group

print(armor_ref) # Error, used invalidated groupLet's look at it piece-by-piece.

An owning pointer to heap, unique_ptr in C++ speak.

A tagged union, "enum" in Rust speak.

This doesn't have an "(owns)" arrow because in Mojo (which Nick's proposal was for), a Variant is a tagged union, which holds its data inside itself, rather than pointing to its data on the heap.

print(hp_ref)

The hp: Int isn't in a Variant or a collection, so it's pointing into the r group (not a child group), so the compiler can let us use our reference after the damage method.

Or using our more familiar terms: the integer can't be independently destroyed before or after the Entity (its memory is inside the Entity after all), so it's not in a child group, so the compiler can let us use our reference after the damage method.

print(ring_ref)

Now consider ring_ref which points to an item in d.rings.

ref ring_ref = d.rings[rand() % len(d.rings)] # Group r.rings.items[*]

...

...

d.damage(10) # Invalidates refs to r's child groups

# Group r.rings.items[*] is invalidated

...

print(ring_ref.power) # Error, used invalidated groupThat ring is in a collection (the d.rings ArrayList), so it's in a child group r.rings.items[*], so the compiler shouldn't let us use our reference after the damage method.

Or using our more familiar terms: the Ring could be independently destroyed (such as via a remove or append call on the ArrayList), so it's in a child group, so the compiler shouldn't let us use our reference after the damage method.

So, as you can see, hp is in the Entity's group, but a Ring is in a child group.

print(len(rings_list_ref))

Let's do a harder example. Consider the rings_list_ref that points to the whole d.rings list, rather than an individual Ring.

ref rings_list_ref = d.rings # Group r

...

...

d.damage(10) # Invalidates refs to r's child groups

...

print(len(rings_list_ref)) # OkayThat rings_list_ref is actually pointing at group r, not a child group, because the rings ArrayList isn't in a collection (it is the collection). It's in group r (not a child group), which wasn't invalidated, so the compiler can let us use our reference after the damage method.

Or using our more familiar terms: the List itself can't be independently destroyed before or after the Entity (its memory is inside the Entity after all), so it's not in a child group, so the compiler can let us use our reference after the damage method.

That means rings_list_ref is still valid, and we can use it in that print call!

print(s.durability)

Consider s, which points into the hand variant's Shield value.

match ref d.hand:

case Shield as ref s: # Group r.hand.Shield

...

d.damage(10) # Invalidates refs to r's child groups

# Group r.hand.Shield is invalidated

...

print(s.durability) # Error, used invalidated groupdamage could have replaced that Shield with a Sword, thus destroying the Shield.

Because of that risk, the compiler invalidates all of group r's child groups, and catches that print(s.durability) is invalid.

Child Groups, Summarized

To summarize all the above:

- A Variant's element or anything owned by a pointer will be in a child group.

- In other words, a group's child group is the objects that that group owns which can be independently destroyed

- For example, if an ArrayList is in a group, then its contents array is in its child group.

- When someone modifies a parent group, we invalidate all references into any of its child groups.

If any of this doesn't make sense, please help us out by coming to the Vale discord and asking questions! I want to make this explanation as clear as possible, so more people understand it.

Where do groups come from?

So we know what a child group is, but how does one make a group? Where do they come from?

Local variables! Each local variable has its own group. 14

Let's look at main:

fn main():

entities = List(Entity(10, 10), Entity(12, 7))

attack(entities[0], entities[1])The local variable entities introduces a group, containing only itself. As we've just discussed, this group contains several child groups (that are not created by local variables). When we invoke attack, we're passing the child group that represents the elements of the entities list.

Additionally, groups can be combined to form other groups. This would also work:

fn main():

entity_a = Entity(10, 10)

entity_b = Entity(12, 7)

attack(entity_a, entity_b)This time, when we invoke attack, we're passing a group that represents the "union" of the two local variables.

So, to summarize where groups come from:

- Each local variable forms its own group.

- Multiple groups can be combined into one.

- Variants and collections inside a group can form child groups.

What about heap allocations? For example, if we had a var x = Box[Entity](10, 10). In this case, the local variable x has a group. The Entity it's pointing to is a child group.

Isolation

There's a restriction I haven't yet mentioned: all items in a group must be mutually isolated, in other words, they can't indirectly own each other, and one can't have references into the other. In other words, in the above example, an Entity cannot contain a reference to another Entity.

With this restriction, we know that e.g. d.damage(42) can't possibly delete some other Entity, for example a. More generally, we know that if a function takes in a bunch of references into a group, it can't use those to delete any items in the group.

I won't go too deeply into this, but if you want an example of why this is needed, try mentally implementing an AVL tree with the system. AVL tree nodes have ownership of other nodes, so any function that has the ability to modify a node suddenly has the ability to destroy a node, and if nodes can be destroyed, we can't know if references to them are still valid. That would be bad. So instead, we have the mutual-isolation rule.

Functions' Group Annotations

Here's a smaller version of one of the above snippets.

fn attack[mut r: group Entity](

ref[r] a: Entity,

ref[r] d: Entity):

ref contents_ref = a.armor_pieces[0] # Ref to contents

d.damage(3)

print(contents_ref) # InvalidAt long last, we can talk about the [mut r: group Entity]! These are group annotations. They help the compiler know that two references might be referring to the same thing. Note that the call site doesn't explicitly have to supply a group for r, the compiler will infer it.

The use of the group r in the signature of attack informs the compiler that even though d.damage(3) is modifying d, this may change the value of a, and therefore we need to invalidate any references that exist to child groups of a.

Stated more accurately, d.damage(3) is modifying group r, so it invalidates all references that point into r's child groups (like contents_ref).

These group annotations also help at the call site, like in this example:

fn main():

entities = List(Entity(10, 10), Entity(12, 7))

attack(

entities[rand() % len(entities)],

entities[rand() % len(entities)])Specifically, this invocation of attack is valid, because attack has been declared in such a way that the arguments are allowed to alias. This information is explicit in the function signature (in attack), so it is visible to both the programmer and the compiler.

A More Complex Example

Let's see a more complex example, and introduce a new concept called a path which helps the compiler reason about memory safety when calling functions.

Here's our main function again:

fn main():

entities = List(Entity(10, 10), Entity(12, 7))

attack(

entities[rand() % len(entities)],

entities[rand() % len(entities)])And here's something similar to our attack from before, but with a new call to a new power_up_ring function:

fn attack[mut r: group Entity](

ref[r] a: Entity,

ref[r] d: Entity):

ref armor_ref = a.armor # Ref to a's armor

# Modifies a.rings' contents

power_up_ring(a, a.rings[0])

# Valid, compiler knows we only modified a.rings' contents

armor_ref.hardness += 2As the comments say, power_up_ring is modifying one of a's rings, and it doesn't invalidate our armor_ref.

To see how that's possible, let's see power_up_ring (note I'm taking some liberties with the syntax, a much shorter version is in a section below):

# Wielder Entity's energy will power up the ring.

# Changes the ring, but does not change the wielder Entity.

fn power_up_ring[e: group Entity, mut rr: group Ring = e.rings*](

ref[e] entity: Entity,

ref[rr] a_ring: Ring

):

a_ring.power += entity.energy / 4Let's unpack that fn line:

- e: group Entity means: e is a group of Entitys. Note how there's no mut here.

- mut rr: group Ring means: rr is a group of Rings. This one is mut.

- = e.rings* means: rr points to Rings in e's Entitys' field .rings. We call this a path.

With this, the caller (attack) has enough information to know exactly what was modified. 15

Specifically, attack knows that Entitys' .rings elements may have changed. Therefore, after the call to power_up_ring, attack should invalidate any references pointing into Entitys' .rings elements, but not invalidate anything else. Therefore, it should not invalidate that armor_ref.

Inside the function, we see a a_ring.power += entity.energy / 4. Note how it's:

- Reading an Entity

- Modifying a Ring inside the Entity.

The latter is also why we have mut in mut rr: group Ring; the compiler requires a function put mut on any group it might be modifying.

This is also something that distinguishes this approach from Rust's. Partial borrows can do some of that, but generally you can't have a &Entity while also having an &mut Item pointing to one of the Entity's items.

Well not exactly. Technically, only the .power field is being modified, but power_up_ring is saying that anything inside Ring might have changed.

Paths

I want to really emphasize something from the last section:

mut rr: group Ring = e.rings*

This is the key that makes this entire approach work across function calls. Whenever there's a callsite, like attack's call to power_up_ring(a, a.rings[0]), it can assemble a full picture of whether that call is valid, and how it affects the code around it.

When compiling attack, the compiler thinks this:

- The caller (attack) calling power_up_ring(a, a.rings[0]).

- The callee's first argument's group e.

- The callee's second argument's group is e.rings*, which corresponds to a.rings[0] in the caller.

- The callee's second argument's group is mut, so the callee will modify things in it.

- Therefore, the callee will modify the caller's a.rings's elements' contents.

This path is how the caller knows what the callee might have modified. That's the vital information that helps it know exactly what other references it might need to invalidate.

Syntax

If you thought that syntax was verbose:

fn power_up_ring[e: group Entity, mut rr: group Ring = e.rings*](

ref[e] entity: Entity,

ref[rr] a_ring: Ring

):

a_ring.power += entity.energy / 4...that's my fault. I wanted to show what's really going on under the hood.

Nick actually has some better syntax in mind:

fn power_up_ring(

entity: Entity,

mut ref [entity.rings*] a_ring: Ring

):

a_ring.power += entity.energy / 4Way simpler!

The approach, summarized

With that, you now know all the pieces to Nick's approach. Summarizing:

References to object vs its contents: there's a distinction between an object and its contents. We can have as many references to an object as we'd like. Mutations to the contents will invalidate references that point into the contents, but don't have to invalidate any references to the object itself.

Child groups let us think a little more precisely about what mutations will invalidate what references to what contents.

Group annotations on the function give the compiler enough information at the callsite to know which references in the caller to invalidate.

Does the approach really not have unique references?

When I was learning about the approach, I was kind of surprised that it had no unique references. They seemed inevitable. 16 In his proposal, Nick even mentions this example:

fn foo[mut r: group String](names: List[ref[r] String]):

p1 = names[0]

p2 = names[1]

p1[] = p2[] # Error: cannot copy p2[]; it might be uninitialized.The final line of the function first destroys p1's pointee (implicitly, just before assigning it a new value), and then copies data from p2's pointee. (By the way, postfix [] is Mojo-speak for dereference, so p1[] is like C's *p1)

The challenge here, as he explains, is that p1 and p2 might be pointing to the same object. If so, one or both of these objects might end up with uninitialized data.

His solution mentions using escape hatches in this case, like this:

fn swap[T: Movable, mut r: group T](ref[r] x: T, ref[r] y: T):

if __address_of(x) == __address_of(y):

return

# Now that we know the pointers don't alias, we can use unsafe

# operations to swap the targets. The exact code isn't important.

unsafe_x = UnsafePointer.address_of(x)

unsafe_y = UnsafePointer.address_of(y)

# ...use unsafe_x and unsafe_y here to swap the contents......but this can theoretically be built into the language, like this:

fn swap[T: Movable, mut r: group T](ref[r] x: T, ref[r] y: T):

if not distinct(x, y):

return

# ...use x and y...At first, I saw this and thought, "Aha! distinct hints to the compiler that these are unique references!"

But... maybe not. Instead of thinking of these as unique references, you could think of this as "splitting" group r into two temporary distinct groups.

Throughout the entire proposal, I was expecting the next section to talk about how we inevitably add unique references back in. And as I was thinking ahead, I kept on adding unique references in, in my tentative understanding of his model. This is the problem with being accustomed to conventional borrow checking... it makes it harder to think of any other approach.

Luckily, Nick consistently tried to understand what operations can cause pointers to dangle, and impose as few restrictions as possible while ensuring that dangling pointers are always invalidated. With that in mind, the AxM constraint never arose. It's the same mindset I used to come up with Vale's generational references + regions blend. It must be like art: design constraints lead to inspiration!

Comparison to Borrow Checking

Group Borrowing could be much better than borrow checking.

- It should be much more permissive than borrow checking, and prove a lot more programs correct.

- It should lead to better error messages. Whereas rustc gives errors about abstract borrowing violations, this model should be able to give errors that point out the actual real risks: "you can't use this pointer down here, because it might not be valid anymore because of this modification up here".

- This is particularly important to a language like Mojo, which is designed for Python programmers. The ramp from dynamic typing to static typing to single ownership to borrowing is steep, and this could help.

- Allowing safe mutable aliasing could lead to less people reaching for workarounds like unsafe pointers. In other words, by making safe references more expressive, we can make systems languages more memory-safe in practice.

Though, it might also result in programs that are architecturally similar to borrow checking.

- The mutual isolation restriction might influence our programs' data to look like trees, similar to how Rust's borrow checker does. 17 However, the approach has much more relaxed rules around how we access those trees from the outside (via references in local variables and arguments), which is a nice improvement.

- A line of code that deletes something will invalidate any references to any of its child groups. A similar constraint appears in borrow checking, though it's more relaxed here.

It might be faster than borrow checking in some cases.

- For example, the attack example doesn't need to do repeated hash lookups like in Rust.

- More generally, his approach means we can have more references, and less hashing, cloning, and bounds checking.

But it might be slower in some cases. Not having unique references means it could be challenging for the compiler to compile references to faster noalias 18 pointers. Nick showed me this article to highlight the possible speed differences, and we discussed a few promising options. Perhaps a compiler could:

- Emit noalias for an argument when the argument is the only argument into a certain group.

- Have a special kind of group where all references are guaranteed distinct.

- Notice when the code checks (via if, assert, etc.) that all pointers into a group are distinct, and emit noalias then.

And this model might have downsides:

- Since there's no such thing as a unique reference, it could lead to awkward situations, where we have to convince the compiler that two references don't alias.

- Then again, Rust kind of has this too, in the form of .split_at_mut. It might be easier here?

- This model hasn't been implemented yet and therefore hasn't been proven to work, of course.

So, will this be revolutionary? Perhaps! Or maybe it'll be just a surface-level improvement on borrow checking in practice. Or, it could be the key that unlocks borrowing and makes it more palatable to the mainstream.

It might not actually influence our systems into trees. I suspect that in a multi-layered architecture, upper layers can have many aliasing mutable references to objects in layers below, while still allowing people to modify those lower layers' contents.

If that turns out to be true (Nick and I are still exploring it) then he's found a way to make borrowing work for some DAG-shaped program architectures, rather than just strictly tree-shaped architectures.

On top of that, if we compose this approach with linear types, I think we can get at least halfway towards compile-time-memory-safe back-references, which would unlock a lot of things like doubly-linked lists, back-references, and delegates. TBD whether that works, but that would be pretty exciting.

I'm being a bit vague, but drop by the Vale discord server and I can explain my crazy thoughts a bit more.

noalias is an annotation given to LLVM to tell it that no other pointer will be observing the pointed-at data while the pointer is in scope. It helps the compiler skip some loads and stores.

Where we go from here

Where does the idea go from here? Not sure!

This idea is still new, and could evolve in a lot of different directions.

- Maybe we'll discover some ways we can decompose it into multiple orthogonal mechanisms, like how implementation inheritance (Java's extends) is really just implements+delegation+composition. 19

- Maybe we'll discover that this pairs perfectly with another mechanism, like reference counting (or generational references? Who knows!).

- Maybe we'll find a different way to communicate across inter-function boundaries, so that child group invalidation can be more precisely expressed and controlled.

- Maybe someone will find a way to make these groups (mutably) alias each other! 20

In the grimoire, I hinted about a hypothetical blend of reference counting and borrowing that we don't yet know how to make. I mention that one possible path to it will be to combine various memory safety techniques together. This could be one of them.

So regardless of how well this model does on its own, it could be an amazing starting point for hybrid memory safety models. I wouldn't be surprised if one of you reads this, reads the grimoire, and discovers a clever way to blend this with existing mechanisms and techniques. Let me know if you do, and I can write an article like this for you too!

By this I mean, you can accomplish anything with extends, if you turn the base class into an interface and a struct (like Dart does), and your "subclass" would instead implements the interface, contain the struct in a field, and forward any calls from that interface into that struct.

This would have to be opt-in of course. Non-aliasability is a good default, because it allows the compiler to perform optimizations (e.g. keep values in registers for longer) that can actually have a dramatic impact on performance.

Conclusion

Once you understand it, the concept is pretty simple in hindsight.

Of course, it pains me to say that "it's simple", because it makes it seem like it was easy to discover. I know from personal experience just how hard it is to come up with something like this... it takes a lot of thinking, trial and error, and bumping into dead ends. 21

And we must remember that Nick's model is a draft, and is still being iterated upon. As with any new model, there will be holes, and there will likely be fixes. Vale's region borrowing design fell apart and was fixed a few times yet is still standing, and Nick's model feels even cleaner than regions, so I have hope.

If there's one big thing to take away from this post, it's that we aren't done yet. There is more to find out there!

That's all! I hope you enjoyed this post. If you have any questions for Nick, he hangs out in the Mojo server (username nick.sm), or feel free to ask questions in the r/vale subreddit or Vale discord server.

And most importantly, if you enjoy this kind of exploration, sponsor Nick!

Cheers,

- Evan Ovadia

Designing region borrowing for generational references took me years. And before that, I was almost broken by 32 iterations of a (now abandoned) Vale feature called "hybrid-generational memory". Near the end there, I was so burned out on the highs and lows of breaking and repairing and improving that feature, that I almost gave up on language design entirely.

Nick told me he's gone through a similarly grueling experience trying to nail down a design for his "groups". I'm glad he stuck with it!